Keyboard journeys – history of the # hashtag

May 19 2022

We might use this little pointy character everyday in our marketing but how did that all begin. I put myself on a quest to find out more.

My Apple keyboard, bought around 2005, is still in pretty good shape. In fact, the E key, typically first to disappear is only just showing signs of wear. But, because it’s coming up to 20 years old one thing you won’t find on it is a # sign. It’s there, combine Alt + 3 and up it pops. But why isn’t it sitting loud and proud on key 3?

Wind back to 2005 and none of us knew how to tweet, tag or post. In fact in the UK apart from using it occasionally on a push button phone for a ‘press # to …’ kind of thing, hashtag wasn’t part of our language at all.

And that got me intrigued. What’s the story behind this quirky pointy symbol? What were we doing with it before Social Media took it in hand? Thanks to some fabulous enthusiasts I met online, poking around the internet, and the knowhow of the British Library I got myself some answers.

Not hot off the press

The invention of Gutenberg’s movable-type printing press was a communications revolution every bit as significant as the internet’s introduction over 500 years later. It made fast text reproduction (that’s relatively fast compared to copying out by hand) possible with fairly basic machine, revolutionising the speed and reach of the written word.

So, how did they handle the hash back then? I got in touch with Norwich Printing Museum, one of the UK’s few remaining working print museums, with machinery and type dating back to 1815.

Hopeful of turning up stories of usage across the decades I put my questions to one of the museum’s compositors, Gerry Morris. Compositors arrange text and illustrations for printing books, magazines and newspapers so if there’s a symbol they have seen it.

And it turns out that the # is one Gerry has never come across whether at the museum or during his career. Gerry did his apprenticeship at the East Anglian Times newspaper in the 1960s, moving to London in 1970 to be a print buyer at BBC Publications. A couple of job changes later and he was involved in printing national newspapers. In all that time, and while at the museum, he’s only ever used the # for one special function.

And that’s as a fill-in for the musical sharp symbol. The two are pretty similar and close enough for it to be clear what’s meant by F# even if not an exact match.

If I wasn’t going to find an ancient use for a hashtag among our printing presses, would UK typewriter keyboards be able to reveal more?

To be honest, that wasn’t looking too hopeful either according to UK typewriter enthusiast Mark Irving. Both his grandly titled 1960-ish IBM Executive machine and a 1925 Remington Portable were both sold into the British market as far as he knows and neither has a # symbol.

Then compositor Gerry mentioned his brother-in-law in New York, has a # in his address. Perhaps America would be the place for answers? Maybe, but first a trip to the British Library.

The # is in the detail

It was a tall order but would finding the oldest book in the British Library featuring a hashtag shed any light on its history? A quick search for ‘#’ and ‘hashtag’ within any title on their Explore the British Library catalogue only gave #trending / an anthology by the First Story Group at Bulwell Academy published in 2013. Cute but that’s from way after the # was first used in social media, so nothing for us there.

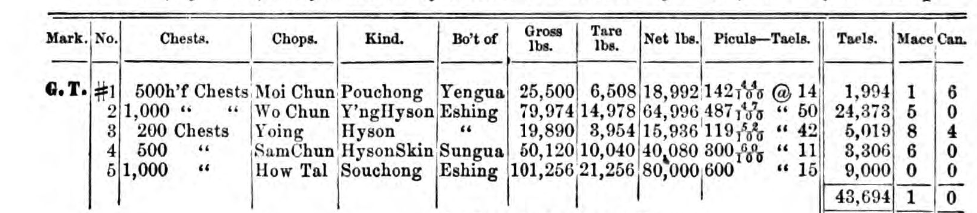

Enlisting the help of one knowledgeable curator widened the search but also made it clear that finding the oldest book featuring a # anywhere in its text would mean searching every catalogue at the British Library. Something unfortunately I and this blog post didn’t have time for. But then something turned up. There in column two, among the pages of An Elementary Treatise on Book-Keeping by Single and Double Entry, designed for Common Schools, etc. by Samuel Worcester CRITTENDEN I found my oldest hash to date.

The book was published in Philadelphia in the US in 1853. Where we might write No.1, the Americans use #1, so perhaps America would fill those knowledge gaps after all.

Going stateside for answers

Contacting the brilliant Virtual Typewriter Museum gave me a lead to meet a group of keyboard enthusiasts who come together online at GroupsIO. I’m really grateful for what they had to share.

Group member, Brian Brumfield, set some helpful context, “A typewriter’s first purpose was industrial: to speed up the accounting of shipping and trade.” Which makes perfect sense thinking about the entry found in the book-keeping text at the British Library. It might come with other functionality, but today’s spreadsheet is basically an electronic representation of what was once done with pencil and ruler and then the typewriter before the computer came along.

As Brian puts it, “When you’re trying to conserve space and speed up processing, symbols like @ and # had the same purpose – to streamline type and reduce space needed on crowded forms.” It turns out that in the US the # symbol used after a number, like 3#, replaces the word for the imperial ‘pound’ weight in the way we may use 3lbs.

Enjoy this accounting shorthand from Brian that shows the symbols in action:

Apples @ $.03 per # qty 200# …. $6

So, that’s 200lbs of apples bought at 3 cents per pound costing $6

Michael Hurley helped further by adding that putting the # behind a number to shorthand pound weight happened about 200 years before being used as a stand-in for No. in the mid 1800s. But, by the time the typewriter came about both hand-drawn symbols were common in the US so the symbol was added to state-side keyboards very early on. So, how early is early?

Making its way onto the page

A history-making machine that this fab community had plenty of facts about was the Remington Standard No 2. As Peter Weil puts it, “ the ‘Perfected’ # 2 Type-Writer was first shown at the 1876 Exposition in Philadelphia and commercially introduced the next year.” Versions of the #2 made from 1877 to around 1882 only added the # symbol as a special order until marketing the machine moved from in-house to a firm with the catchy title of Wyckoff, Seaman’s and Benedict in 1882.

From then on, the # seems to have been a permanent fixture, usually sharing the key with number 3. Glenn Gravatt is proud owner of what he believes is the fourth oldest surviving Remington Standard No 2 machine, with a serial number dating it to 1883. And there is our little friend the # sign on the 3 key.

4th oldest remaining Remington No 2 typewriter, image courtesy of Glenn Gravatt

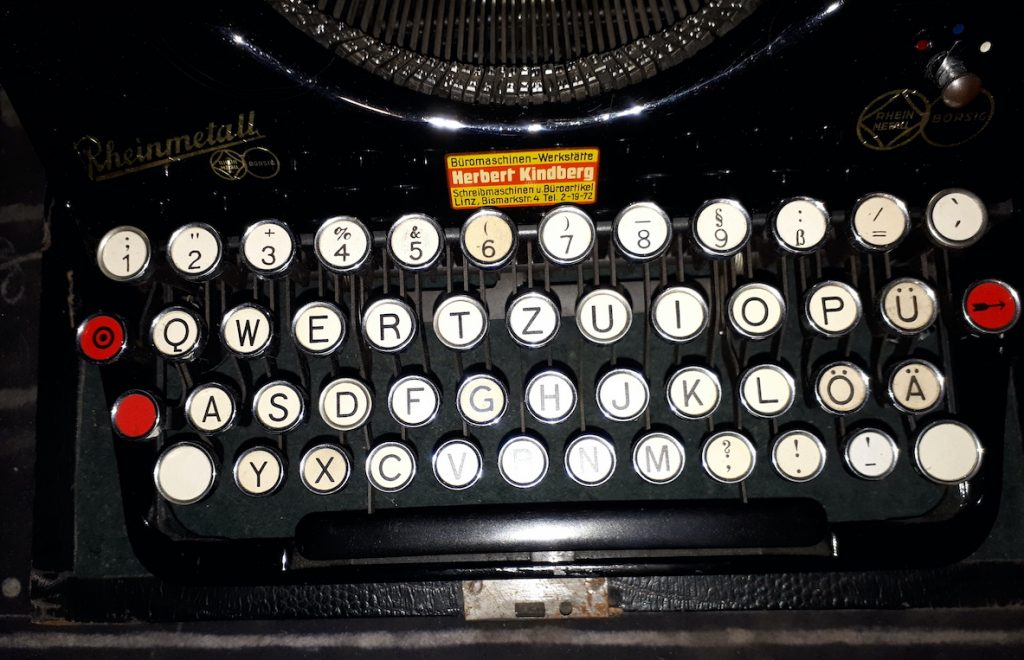

The # key wasn’t alone in starting out as a non-standard feature. A huge amount of typewriter key customisation went on to for machines to be sold around the world. Even today, we’re not all staring at a QWERTY keyboard.

An online archive of Remington typewriter order sheets gives a taste of what they were prepared to do for different markets, businesses and sectors. I’ve been reliably informed that among some of the more unusual bespoke typewriter keys made were a VW symbol for the Volkswagon company, apothecaries’ machines with special characters for producing prescriptions and, more infamously, the Nazi SS who had their symbolic lightning-bolts as a custom key.

Early typewriters made in or for Canada, a country that at the same time is part of the British Commonwealth and North America, feature keyboard layouts with both influences. The Canadian-made 1914 Remington 12 machine owned by writer Adam Basquill doesn’t have a # key whereas his 1927 Underwood 3 US-made machine, built for the Canadian market, does.

Here’s a shot of Adam’s partially restored Rheinmettal Borsig German typewriter from 1938. Plenty of special characters here for a German audience but no hash.

1938 Rheinmettal Borsig typewriter, image courtesy of Adam Basquill

And, after the typewriter?

There’s loads on Wikipedia about the rise of the # from our typewriters and into our computers but this didn’t happen until well into the 20th century.

In a nutshell the top facts are:

- Used in IT to highlight specific pieces of text or actions from 1970 onwards

- Picked up in 1978 for the C programming language to indicate special keywords,

- Adopted for Internet Relay Chat (IRC) networks around 1988 to label and organise groups and topics.

- Tagging topics like this inspired internet consultant Chris Messina to tweet the first ever hashtag on 23 August 2007 “How do you feel about using # (pound) for groups. As in #barcamp [msg]?”

- Twitter didn’t immediately adopt the # but it didn’t matter, the convention quickly caught on.

If reading this has whetted your appetite for more, then look out for a copy of the book Shady Characters by Keith Houston. It’s a delightful delve into the history and folklore of ampersands, interrobangs and other typographical curiosities. As the book tells us, “Every character we write or type is a link to the past, and in today’s writing – be it printed, electronic or handwritten – this history stares right back at us.”